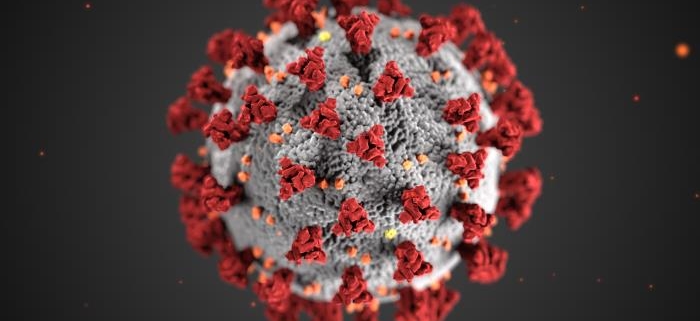

Operating in The Pandemic: What we have learned so far.

In January 2020 I read a couple of books about the 1918 flu. Within a few weeks it became clear that for the time being these books remained the state of the art in virus mitigations and public health.

In March as the state shut down business, we were notified by several customers that we were considered essential and expected to keep operating. This raised a lot of questions – particularly how do we keep our employees safe?

Guidance from the government was initially vague, but like any safety challenge there is a systematic way approach the issue.

- Relying on the 1918 teachings we immediately supplied masks, and instituted social distancing.

- Our employees were used to working on medical products, so we had the necessary PPE and hygiene supplies along with the training in how to use them.

- Our two shifts modified there schedule so there was no overlap. Extra end-of-shift cleaning protocols were implemented with the between shift being done by management as a further check.

- To reduce the office density, one half of the office staff went on a work-from home schedule. As we already had the IT tools in place, this was basically seamless.

- To eliminate ambiguity, we wrote policies to dictate the response were an employee to get Covid.

- To minimize exposure a staffing freeze was implemented, and no visitors were allowed in the plant.

Two further measures were taken which may have been critical:

- Three stand-alone filtration devices were acquired and located in areas where distancing was more difficult.

- We ran an exhaust fan all winter. Combined with several air inlets this allowed us to run “negative pressure” in the entire plant. Despite the impact on our heating bill, we feel this was one of the most important mitigations.

While the pandemic is not over, these measures along with everyone’s compliance has kept Covid out of Micrex.