The One Best Way (Part 4): Creativity

Looking closer at whether there is one best way to solve a particular problem: let’s look at creativity and bringing it into your company. Can it be taught? Probably to some degree. How to invent, be more creative, or develop new products has always been part art and part science.

George Bernard Shaw wrote in Man and Superman — “Bob: I’m so discouraged. My writing teacher told me my novel is hopeless. Jane: Don’t listen to her, Bob. Remember: those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.”

While there are individuals and firms that claim to teach creativity, I suspect that if anyone really had the key, it would have been more remunerative to make inventions, than to teach others how to do it.

This is evident in the investment business. Investment advisors are everywhere, but few have their own success to show for it. The successful investor is generally unable or unwilling to part with his knowledge unless highly rewarded.

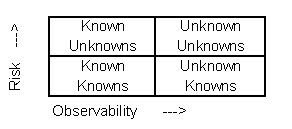

This is relevant when it comes to hiring consultants. While it is desirable to keep some tasks in-house, if you do not have creative capacity on staff, contracting out – bringing the creativity in – provides a cost-effective solution.

Going back to the original question: Is there one best way to add creativity to your company equation? No. It depends entirely on the industry, the company, the culture, the age, education, experience of the staff and the size. The charge led by “Here is how they do it at Intel” can be a disaster for the wrong company.