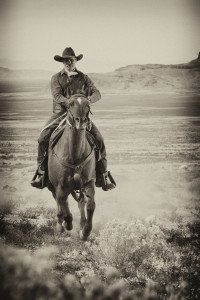

The One Best Way (Part 6): Cowboy Coding

Software development is hard. Whether it is combining incredible levels of creativity and complexity, or talking about the high rates of failure – the debate about software design and development techniques has a lot of relevance to other disciplines.

We have already touched on the use of a grand design. This is sometimes referred to in software as “Waterfall Design”, as all parts of the product are supposed to flow together and work as one in the end.

At the other end of the spectrum is “Cowboy Coding” where the lone programmer is given freedom to do what seems right. There are “nicer” versions. For example, “Agile Programming” has the patina of an intellectual framework.

B. F. Skinner said, “A first principle not formally recognized by scientific methodologists: when you run into something interesting, drop everything else and study it.”

Just another Harvard trained cowboy.